System Design 6 - Key Value Store

To Reinvent Redis Cache

Introduction

We’re slowly getting to designing for more specific use cases, but for the time being, let’s discuss one of the things before doing an entire system.

This time, we’ll be looking into a Key-Value store. We’ve mentioned these previously with Redis, Memcache and other caches. We’ve also

dealt with them before when talking about consistent hashing - because the reason we’re hashing is mostly to save to a key value store.

So, without further ado, let’s talk about key-value stores.

What is Key-Value Store

Most likely, all developers have already dealt with it in some shape or form. In data structures, a hash-table is a key-value store. In JS, any object is a key-value store.

Consider the following example:

const arr = [];

const obj = {};

for (let i = 0; i < 10_000_000; i++) {

arr.push({ id: i});

obj[i] = { id: i};

}In the code above, I’ve created a very simple array and a key-value store (or object, or hash-table - it’s all the same).

Now, when I want to get an item with index where id == 5000, I’d simply do:

const itemFromArray = arr.find(i => i.value === 5000);

const itemFromObj = obj[5000]Now, of course I could use direct index access on the array in the above example. But we’re not always able to ensure arrays are in order. Furthermore, we’ve mentioned that unique identifiers, such as uuids, are used. We can’t use these as keys with arrays. However, with objects, we can index by string.

Sidenote:

Arrays can also have keys if you misuse them. I am aware of that fact.

JS Arrays are objects deep down and can be treated as such. But that is not the point of this post.

In the above example, we’d have to iterate over the array, making the operation slower. With key-value stores, the complexity is log(1). That is one of the reasons why key-value stores are so fast.

Key-Value always have 2 components:

- Key - Unique identifier for the entire value.

- Value - The value correlating 1:1 with the key.

NoSQL databases are basically enhanced key-value stores. That is also the reason why they are so fast for massive data that are not relational.

Key-Value stores often have 2 functions:

getfunction to retrieve a valueputfunction to set a value.

The most basic Key-Value store was already used in previous chapter:

const keyValueStore = {};

const get = (id) => keyValueStore[id];

const set = (id, value) => (keyValueStore[id] = value);

export { keyValueStore };Or, JS Map object is also a Key-Value store.

In terms of system design, we are talking about the same thing. However, we scale it up. We scale it way up. Rather than from a single program, we built entire caching and databases out of it. We use it for some form of data persistence or faster access. And as mentioned, examples include:

And because there are 14 competing Key-Value stores, let’s build one that will fit all purposes

Key-Value store design

So, now that we established what a key value store is and how we can make a system out of it, let’s design a single server key value store!

Oh wait, we’ve already done that. Because that is what we just did. A piece of code that lives on a server. The entire problem comes when we go distributed.

But why do we want to go distributed? Well, as mentioned before, you can only go so far until you run out of memory. So, having a distributed key value store allows for more data.

And to create a distributed store, as is the case always in system design, we need to make some tradeoffs.

CAP theorem

The CAP theorem states that a distributed data store can provide only 2 of 3 guarantees:

- Consistency (C)

- Every read receives most recent data (no stale data)

- Availability (A)

- Every request receives a response, but not necessarily latest data

- Partition Tolerance (P)

- System operates even though 2 partitions can’t communicate

So, we’ll always have either CA, or AP, or CP, but not all of them. Well, there are a bunch of choices!

But are there? Because if you look at the partition tolerance, it basically states that it works if network is down. Which is impossible in system design across different countries.

So, in the real world, we’ll always have to choose between availability and consistency, because we must never sacrifice partition tolerance.

Let’s take a look at a specific example. Consider you are a bank. Now, ideally you want your system to be always available and consistent. But, if you have to choose only one, what would you choose?

- If you want availability, then you sacrifice consistency.

- Your clients may try to work with money they don’t have because they still see old data

- If consistency, then you sacrifice availability

- Your clients want to pay with money they have, but they temporarily can’t

Now, this is extremely simplified example, but if I consider myself as a client of such bank, I’d always want the consistency. I want to know how many funds I have at my disposal. If I think I have way more money on my bank account than I have, I could do some serious damage to my finances because I could buy something I can’t afford. However, if availability is sacrificed, I can’t buy the things now, but I’ll still be able to buy it in a couple hours.

Let’s take a more technical look. Keep in mind we are talking about distributed systems.

Consider that there are 3 different stores that contain the data, and 2 of these nodes receive a write request. When it is finished,

it is replicated to other nodes so that the data is consistent across all servers.

If consistency is chosen over availability, then all write oprations must be blocked until the last write operation has been processed. If there’s a network error, subsequent operations are still blocked until the inconsistency has been resolved. This is where availability is sacrificed - The tools are not available because of ongoing operations.

If availability is chosen over consistency, then you accept reads even though the data might not be up to date. This means that you perform write on 2 of the nodes, and read on a third one. While previously you’d wait because you require consistency, in this case, you can return the stale data. An example of this can be facebook posts or google search results. While they are critical in their business to have these available with the latest state, it’s not necessarily mission-critical to always see latest data.

Key-Value Store Requirements

Let’s put forth some requirements for our system:

- The size of a key-value pair is less than 10KB

- It is possible to store big data

- High availability

- High scalability

- Automatic scaling

- Tunable consistency

- Low latency

To achieve these, we’ll need to understand core components and techniques used to build such a store:

- Data partition

- Data replication

- Consistency

- Inconsistency resolution

- Handling failures

- System architecture diagram

- Write path

- Read Path

Data partition

We’ve already discussed data partition in the previous chapter. If you’d like, read on that there.

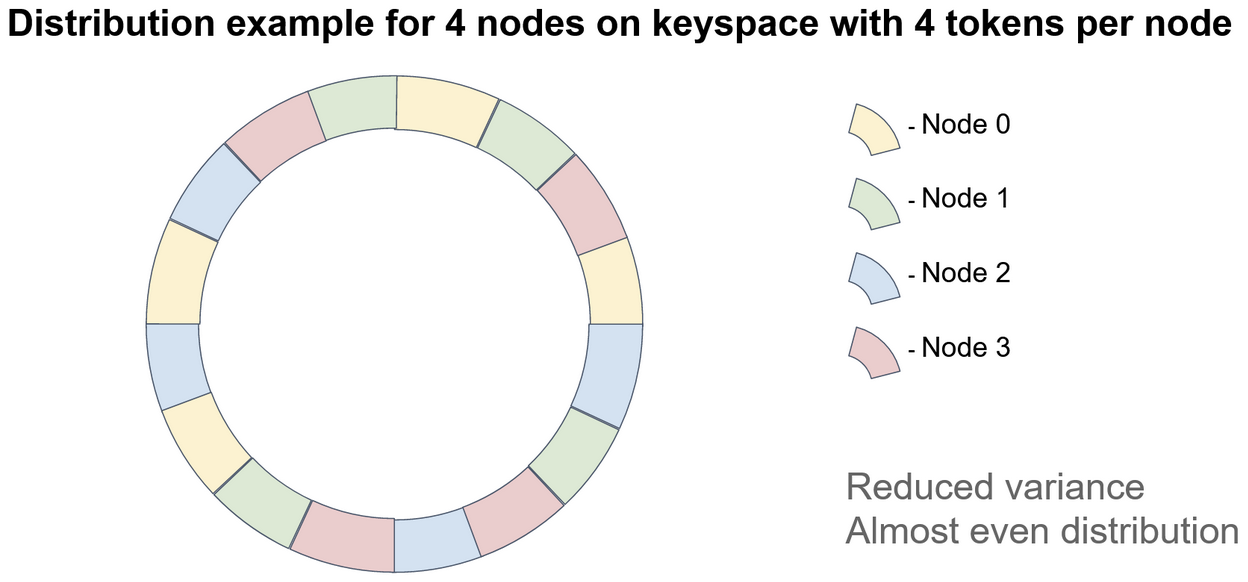

The short story is that we define the data across multiple servers with abstract, virtual nodes, based on hash key. This allows for more even data distribution and trustworthy system. It will also immediately solve scalability as we can add or remove servers as we go.

Data replication & Inconsistency

So, we want to have high availability and consistent data. But what if one of our servers goes down? If we remove it, we’ll just shuffle the data around, but what if a server will go down unintentionally, we could lose some data. To deal with that, we’ll need to do replication.

We already know that:

- Key-Value stores use hashes to store data

- Hashes are defined so that they can be stored in a “Hash circle”

- Hash circle defines hash ranges upon which it stores data

To remind ourselves, let me put the virtual node ring distribution:

Now, consider that data is stored to the Node 3 in top right corner. Now, if the Node 3 server fails, it means all red nodes are removed. So, for better reliability, we’d

replicate the data to the nearest Nodes. How many replicas do we create? Well, it depends on the tradeoff we want.

- The more replicas we create, the more reliable the system is

- The more replicas we create, the less available the system is

Usually the replicas are not added everywhere, but to a couple nearest nodes. If we replicated to all other nodes, then everything would have all data and it would be slow.

Let’s put a couple definitions here to understand this better:

Nis the number of replicasWis the number of write operations. A write operation is successful when it was acknowledged by W replicas.Ris the number of read operations. A read operation is considered successful when R replicas have acknowledged it.

This is called Quorum Consensus

So, if the number of replicas is 3, then when we perform a write operation, it’s sent to 3 servers.

- If W is one, it means that write operation is performed on all 3 replicas, but it cares only about a single response

- If R is one, it means read operation is performed on all 3 replicas, but it only cares about a single response.

What does it mean? Well, we are going to write to 3 different key-value stores (or rather, a distributed key-value store). If we’d wait for all of them to acknowledge the operation, it might take some time, but the latest data is on multiple nodes.

We could simplify this to:

- If R = 1 and W = N, then the system is optimized for fast read

- We care about the first read response, we don’t care about all servers together

- If R = N and W = 1, then the system is optimized for fast write

- Once the first write is successful, we go back to working state. But for reading, we need all replicas responses

- If W + R is greater than N, strong consistency is guaranteed

- If there are 3 replicas and we wait for 2 writes to finish, we wrote the data to multiple sources and we know it is consistent

- If there are 3 replaces and we wait for 2 reads to finish, we got result from multiple sources and we know it is consistent

- If W + R is less than N, we can’t confirm strong consistency

So, again, the number of replicas and read/write operations on multiple sources are tools we can use to achieve consistency, but it’s a tradeoff with latency.

Going further, we can define 3 consitency models here:

- Strong consistency - Any read operation returns value corresponding to the latest write. No stale data.

- Weak consistency - Subsequent reads may not be the most up-to-date. Stale data are possible

- Eventual consistency - A form of weak consistency. With time, all updates are propagated and all replicas are consistent.

The strong consistency, as mentioned before, will not accept additional reads/writes until all replicas have latest data (W = N).

The weak consistency is again flipped around. These can be for fast reads.

With the eventual consistency, we’ll again return stale data. However, we will have to perform inconsistency resolution. One of the techniques we can use is versioning.

Consider the following example:

- A user opens an application and changes his name.

- At the same time, the user changes his name from his mobile phone.

Now, both can hit different servers and both think their update is the correct one. A vector clock is a common technique used here.

In short, a vector clock is a (server, version) pair. Basically, whenever a data is saved, we’ll also save information about which server it’s been saved to, and what version of the datum it is.

- If only one server exists, every version would be simply increment of the previous version

- If multiple servers exist, then the clock value would increment the last version corresponding to the server.

- If the entry does not exist yet, create it with version 1

So, with the original example, if it would be on a single server, then there is no inconsistency - last to be processed is the last one. However, with multiple servers, we don’t know which is the last one when we replicate the data.

Consider the following example - A user changes his name 3 times, with the last one being from multiple devices simultaneously

- The first write is handled by

server 0, defining(s0, 1)on the vector clock - The second write is handled by

server 0, defining(s0, 2)on the vector clock - The third write is handled by

server 0andserver 1, defining:(s0, 3)- note thats1is not present(s0, 2); (s1, 1)- note thes0is present with its last state from this server PoV

- The last 2 writes are reconciled (based on strategy defined by us, we could take either of them)

- A final write happens on

s0, resulting in final state of(s0, 4);(s1, 1)(increment ons0)- The final write could be done by

s1, resulting in(s0, 3);(s1, 2)(increment ons1version)

- The final write could be done by

There are 2 major downsides to this approach

- Space limit - 3 writes caused more versioning on one server than the number of writes. This could get out of hand.

- To resolve this, we can set a threshold and reset versioning when we deem fit

- The versioning itself doesn’t fix anything - we need to add complexity to reconcile the conflicts. It only gives us information with which we can resolve them.

Handling failures

As is often the case, with large systems, failures are not inevitable but common. We need to handle them in a way that they can resolve from themselves and be able to detect them.

To detect a failure, we often do not trust monitoring from a single source.

- Consider a node wants to save data to another node but can’t. However, the node is available, just for some reason the two can’t communicate together

- The node is accessible from another node, confirming it works

- The server is working, but a single link is broken

- We don’t want to make drastic changes because of a single link

To fix that, we could have all nodes talking to one another - Broadcasting. However, with many servers, this might be too inefficient.

Another protocol we could use is the Gossip Protocol (or Epidemic Protocol).

- Each node has its own counter and increases it with time (

heartbeat) - The node sends this counter to other nodes, letting them know that it is working

- The other nodes receiving this information propagate it to next nodes

- If the heartbeat is not increased for a longer (predefined) time, multiple nodes will notice it and can flag that a specific node is down

Once it is confirmed a node is down, we can handle them.

- Strict way with higher consistency is that we’d block all changes made until the issue is resolved

- Sloppy way with higher availability is that the changes are temporarily taken by another node

The sloppy way is very similar to Master/Slave database handling. If the master database is down, a slave database takes its place and performs the write operations. This is pretty much the same thing. At a later point, when the issues are resolved, the server is back online. We resolve inconsistencies and get to original working state.

However, this only works for temporary outages. What if the physical server was completely destroyed by natural disaster? To ensure that the data are not lost, it’s simple - replicate it to multiple servers.

But what if we wanted to replace the server with a completely new instance? Well, we would have to rebuild the data it used to contain.

In comes the Anti-Entropy protocol.

In short, it’s used to compare pieces of data on each replicas and updating others with the latest data. One of the ways to do that is using a Merkle tree to detect inconsistency and minimize the amount of data transferred.

So, what inconsistency are we talking about? Well, let’s consider the example we’ve done before with the 3 writes. The last write is supposed to resolve the inconsistency.

Now, what if the last write doesn’t happen? Then we have 2 sources that differ from one another. How do we find which of them are broken?

- We know the key space that that is used for the hashing function

- We know there are a lot of data in each server

- What do we do now?

Well, first, we take the keys available. Consider that there are 12 keys, one of which has inconsistency - for example, it’s missing

We’re gonna spread these keys into buckets:

For the first server, there will be all values. But for the second one, the key 8 will be missing

Server 1

| Bucket 1 | Bucket 2 | Bucket 3 | Bucket 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 7 | 10 |

| 2 | 5 | 8 | 11 |

| 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 |

Server 2

| Bucket 1 | Bucket 2 | Bucket 3 | Bucket 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 7 | 10 |

| 2 | 5 | 11 | |

| 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 |

Now, we’ll hash all of these:

Server 1

| Bucket 1 | Bucket 2 | Bucket 3 | Bucket 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41 | 49 | 71 | 122 |

| 82 | 59 | 81 | 132 |

| 44 | 69 | 91 | 184 |

Server 2

| Bucket 1 | Bucket 2 | Bucket 3 | Bucket 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41 | 49 | 71 | 122 |

| 82 | 59 | 132 | |

| 44 | 69 | 91 | 184 |

And finally, we’ll hash each bucket (e.g. by hashing the sum of hashes)

Server 1

| 213 | 232 | 323 | 421 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41 | 49 | 71 | 122 |

| 82 | 59 | 81 | 132 |

| 44 | 69 | 91 | 184 |

Server 2

| 213 | 232 | 939 | 421 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41 | 49 | 71 | 122 |

| 82 | 59 | 132 | |

| 44 | 69 | 91 | 184 |

Now, you can notice the the difference between both tables is:

- The Bucket 3 hash

- The Bucket 3 key 8 hash

However, this would work for any nodes inside such a tree. If there were inconsistencies in all 4 buckets, the hash function would reveal them.

So, what do we do with this information? Well, we will build a tree from it! And at its’ root, we’ll have a hash of all the buckets. Let’s hash those:

- Server 1 total hash is 4242

- Server 2 total hash is 2424

And how does this benefit is now? Well, consider the following:

- If the 2 servers have same data, the total hash would be the same. Therefore, there are no inconsistencies to deal with

- If the 2 servers have different data, it’s immediately visible

How do we build the tree? Well, it will basically be a tree of 3 levels!

- Root

- Bucket 1

- Key 1

- Key 2

- Bucket 2

- …

- Bucket n

- Key n - 1

- Key n

- Bucket 1

And by having the hashes, we can immediately see what’s wrong! With the above example, we know that Bucket 3 hash is different, and Key 8 hash is different

In the tree, when we go from the top level, we know which buckets are consistent, and which are not.

Therefore, the number of data to be synchronized is proportional to the differences between replicas, not the data they contain.

- in a real world scenario, the bucket size can be way bigger than 3. It can be thousands

- here can be million buckets for billion keys. With many users, it’s possible

- in such large data, we need to have a fast way to deal with it. The Merkle tree indicates it immediately

System Architecture Diagram

Now we have gone through all the technical considerations. We have achieved consistency, we have learned how to deal with inconsistency, and we found out the tradeoffs various approaches offer.

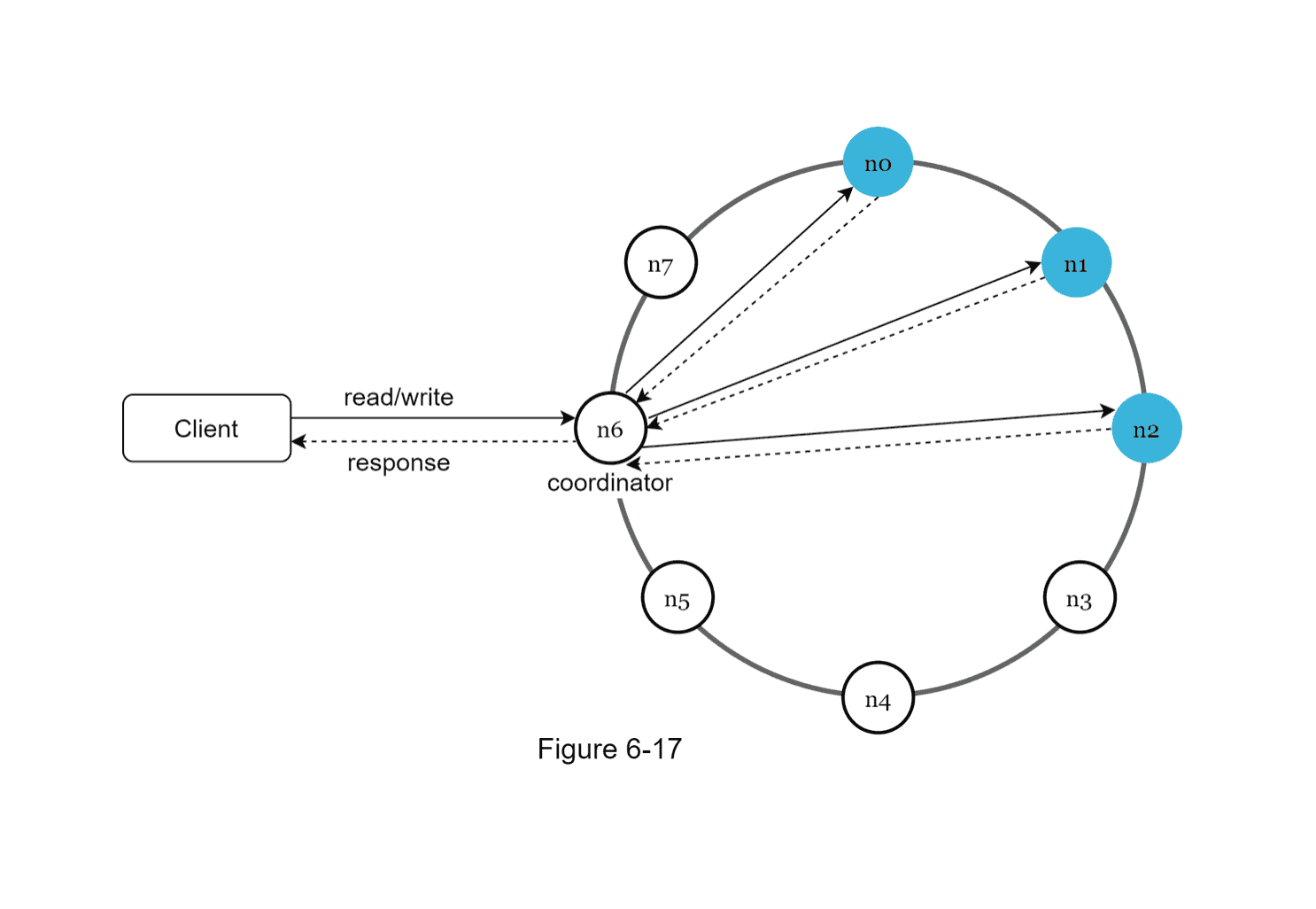

Now, we’ve dealt with nodes for quite some time, but I initially mentioned that there is a web server above them. That’s why we needed to know

how to get the serverIndex in the previous chapter. So, let’s put it all together:

- We have a client that reads into the key-value store

- We have a coordinator who defines into which nodes the data should be written/from which to retrieve the data

- This coordinator also deals with

Acknowledgement. This was discussed mostly in the Data Replication & Inconsistency part - Once the coordinator is done, it returns a response to the client

- This coordinator also deals with

To list all the features:

- Clients communicate through a simple API

get(key)andput(key, value) - Coordinator acts as a proxy between client and key-value store

- Nodes are distributed on ring using consistent hashing

- The system is decentralized and thanks to consistent hashing, servers can be added or removed automatically

- Data is replicated to multiple nodes

- There is no single point of failure

The nodes themselves are fairly complex. Since they are decentralized, they perform a lot of operations, such as:

- Replication

- Conflict (Inconsistency) resolution

- Replication

- Storage

- Failure detection & Failure repair

Writing in the store

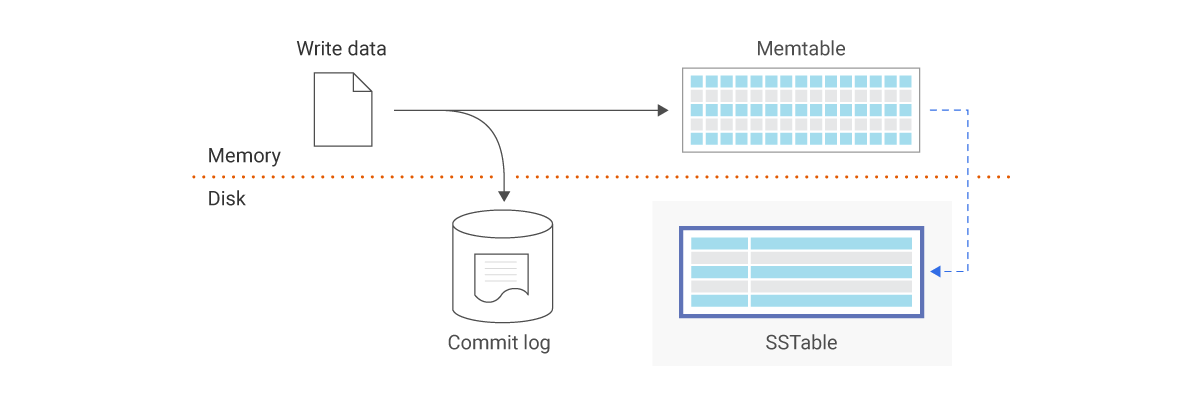

- Whenever a request is received, the write request is persisted on a commit log file

- Data is saved in the memory cache

- When memory cache is full, data is flushed into a Sorted String Table.

- We need to keep the data somewhere if they are not in the memory

The write can be visualized:

Reading from the store

Now, whenever we are reading from the table, we basically read from memory. However, as mentioned before, we sometimes need to read from disk.

Now, we’ve mentioned that it’s stored in a SSTable. While it’s a sorted string of key value pairs, we will have multiple of these, and we need to find which table holds the key so we don’t need to iterate through all of them. Bloom Filter can be used to deal with that.

The final flow would be:

- Read request comes

- First, memory is checked if it there is the result in memory

- If not, bloom filter is used to figure out which SSTable contains the key

- SSTable returns the result of the data set

- The result is returned back to the client

Summary

So, this was a long one! Let’s put it all together.

It is possible to store big data- Consistent hashing to spread load between serversHigh availability- Data replication, multiple data centresHigh scalability- Versioning and conflict resolutionAutomatic scaling- Consistent hashingTunable consistency- Quorum consensusLow latency- Quorum consensus (optimize for read or write depending on what is desired)Handling failures- Sloppy quorum for temporary failures

- Merkle tree for permanent failures

- Cross-datacenter replication

References