System Design 4 - Rate Limiter

Fourth part deals with creating a rate limiter

Introduction

So, you want to be a rate limiter, eh? Do you even know what that means?

Because until recently, I didn’t! So, let’s go ahead and see what a rate limiter is and why do we want them.

What’s a Rate Limiter

So, imagine you’re a company, say Twitter (or X nowadays). Now, you allow users to create a lot of tweets. But what happens if someone is way too enthusiastic about your product and wants to use it maybe a little too much? Or, if there is someone malicious who wants to cause you harm?

Security is a big topic and rate limiter doesn’t deal with the worst issues, but it can help us set some limits for the users.

Now, we’ve played around with twitter estimations in the previous chapter - specifically queries per second and the amount of data we store. Well, let’s take the example again.

300 million monthly active users

50 % use twitter daily

User post twice a day

10 % of the tweets contain media

The data is stored for 5 years

Now, we have defined that user posts twice a day and we have 150 millions daily users. That’s 300 millions tweets a day.

Because creating a post is just an HTTP call to a service with auth token and some payload, a user could create one post, copy the HTTP request, and use cURL to create 300 millions requests. And that user alone can effectively break our estimation design. Our services would break, they would be performing too many operations, and users would be unable to use our preduct due to Denial of Service.

But even if users being unable to use it wasn’t our biggest concern, we would still face many issues - using too much storage, having more services running, and basically raising our service costs.

So, a rate limiter effectively helps us with following:

- Prevents Denial of Service (either intentional or unintentional)

- Reduces costs (limiting resource use means fewer servers and resources used)

- Reduces server load

Now, to get back to the example above, a rate limiter could be applied to the third point in the quote above. If we expect user to post twice a day, we can enforce the expectation to allowing posting only twice a day. Or, we can still expect them to post twice a day, but limit it at 5.

To see specific cases of rate limiting, see for example Twitter docs. They allow different limits for different types of accounts. Another case may be captchas on google if you try to make many requests.

Finally, we have can rate limit on almost anything. Just to name a few:

- Any incoming request (no user-specific)

- Based on IP address

- Based on User ID (logged in users)

Defining the Problem

So, now that we know why rate limiters are good, let’s start thinking about a specific example. As is the case with system design, let’s first put some requirements here:

- Limit excessive requests accurately

- Low latency (should not slow HTTP response time)

- Little memory usage

- High fault tolerance (if there are any issues with rate limiter, the entire system still works)

Now, to add to these, let’s think about 2 more cases. When you’re using google a lot, you’ll probably understand why you’re getting captchas. It is imperative for the user to know why his requests are not working.

Finally, we can have 2 types of rate limiters - centralized, or distributed. Imagine that you’re developing Twitter. Now, as we mentioned before, we can have servers on multiple places - EU, US, anywhere. So, this system is distributed. In contrast to that, if you have only servers in EU, you probably don’t need to care about other servers. So, let’s add two more rules. To recap:

- Limit excessive requests accurately

- Low latency

- Little memory usage

- High fault tolerance

- Exception handling (clear reasoning to users)

- Distributed rate limiting (shared across servers)

Now that we have that defined, let’s continue with high level design!

High Level Design

So, we have a set of requirements. Now, where do we put the rate limiter? It can be either client or server.

- If client, we have no control over the implementation (user can change the JS code he received for example). Furthermore, a new session in client would clear the storage.

- If server, we do have the control

Generally speaking, you never want rate limiter on client. You may want it to disable it on client as well, but savvy users can get around it.

So, scratching the client limiting, we’re left off with server implementation. But which? Because we again have 2 options:

- We have our webserver with middleware functions, meaning every request will call through one more function

- We have our webserver, but before it’s hit, it goes through separate server.

In both cases, the flow will be something like:

- A user makes 3 requests, and rate limiter allows for 2 to go through

- In the first case, the server will receive 3 requests, allow 2 and return HTTP 429 for the third one

- In the second case, the rate limiting server will receive 3 requests, allow 2, and return HTTP 429 for the third one

- The webserver will receive only 2 as rate limiter will have dealt with the third one already

With cloud microservices, rate limiting is implemented using API Gateway. This service allows not only rate limiting, but also SSL termination, authentication, IP whitelisting, and more. This is effectively the middleware.

So, the question to ask is - do we use API gateway or server? Well, as is the case with everything, there is no simple answer. Let’s put a couple points forward to at least have an idea

- API Gateway is easier to implement

- If we do not have the time or lack resources, API Gateway is fast to set up

- With own server, we’d have to write our own algorithms and it takes time

- API Gateway can be limited

- If we want one specific approach because of our business needs, there’s a chance API Gateway won’t support it.

- We have complete control over the implementation with our own server

- If we’re already using API Gateway for other use cases, we may use it for rate limiting as well

So, simply speaking - evaluate if it’s efficient and worth the company resources to implement it ourselves.

Algorithms

So, even though this is about designing a rate limiter, it’s helpful to see a bunch of algorithms. I won’t write code here, but to give an idea:

With the sources above, if you want to, you can deep dive into each of them. To keep this part simple, I’ll do a quick summary.

Token Bucket

Token bucket is probably the simplest of the ones we’ll be covering. It’s well used and easy to implement. In short:

- Each token represents available requests

- There are 5 tokens in a bucket at one time. When a request is called, a token is removed. As long as there are available tokens, requests are not limited

- When there are no tokens, return HTTP 429.

- Tokens are refreshed at a given rate

Note that the 5 is an arbitrary number. There can be thousand tokens available.

Soo, imagine the following design:

- The bucket size is 10

- Tokens are refilled at a speed of 2 tokens per second

That means:

- If the bucket has 10 tokens and 10 requests are sent in one second, all of them pass

- After one second, there are 2 tokens. If 10 requests are sent, only 2 of them pass

- Every second, only 2 more tokens are available.

This algorithm is easy to implement and memory efficient. It allows short-term burst of traffic, but long-term traffics have a hard limit.

Leaking Bucket

The leaking bucket is very similar to the token bucket. However, there is a slight difference - rather than using a bucket, we use a queue processed at fixed rate. To keep it simple, the fixed rate is 2 requests per second. So, what does it mean?

Imagine the same scenario as above:

- If the bucket has 10 tokens and 10 requests are sent in one second, all of them pass

- After one second, there are 2 tokens. If 10 requests are sent, only 2 of them pass

So, this is where the 2 differ. Because with leaking bucket, we allow the requests. But we do not handle them right away - we handle them at a fixed rate

This is where the leaking bucket is different. While with token bucket, the other 8 would get Too Many Requests, in this case, that’s not gonna happen. So what will happen?

- The first part will go as initially - 10 requests are sent in one second

- However, the requests are processed at a fixed rate. So, consider 2 requests are handled each second

- After 1 second, the queue holds 8 requests. After 2 seconds, there are 6 requests. The queue will clear up after 5 seconds.

- Newly incoming requests are added at the end of the queue

Now, it may look like the difference between token and leaking bucket are little - we’re just using queue instead of bucket, right?

Well, consider the following example:

- Token bucket/Queue size is 10 tokens/requests

- Token bucket refills with 1 token per second. The queue processes requests at 1 request per second

- With token bucket, 10 requests come in one second and are processed immediately (10 requests at a time)

- With leaking bucket, 10 requests come in one second and are processed in 10 seconds (1 request at a time)

The main difference is in the last 2 points - leaking bucket allows for stable flow.

Fixed Window Counter

Rather than with data structures, the fixed window counter works with time. Again, we want to limit the amount of requests. How do we do it with time?

- We split time into fix-size windows (say every second in a minute)

- Each window has its counter with defined threshold. Once the counter reaches this threshold, all other requests are dropped

Let’s put this into numbers yet again:

- Consider that we split a minute into 3 time windows - 0-20s, 20-40s, 40-60s.

- We allow a maximum of 20 requests per time window

- Once the counter reaches the threshold, requests are dropped

So, what we can effectively do is send 20 requests in any of these windows (or less). We do not fill queue with old requests, and we allow for some traffic burst. However, instead of refilling (as we did with token bucket), we clean it all up.

There’s one major downside to this. By allowing all requests in a time window, there’s a chance of overloading our system. Specifically:

- Consider 20 requests are sent at the 20th second

- At 21st second, we can call another 20 requests

- Effectivelly, we can “overload” the window by allowing burst traffic in a short period of time (40 requests in 2 seconds while we allow 60 in a minute)

Sliding Window Log

So, previously we’ve had fixed window and identified a big issue with that algorithm. Let’s try to fix it here.

Instead of fixed time, we can have a sliding window. How do we achieve that? Well, this time, we need to keep a little more information about the request

So, what we will do is:

- We take the timestamp of the request

- We store the timestamp in a log

- We compare the log size with threshold

Let’s consider the previous example again, except the first request defines the time window, and we allow for 20 requests from that window.

- 10 request come in at 5th second. The sliding window takes the timestamps and adds them into the log. It will hold it until 25th second

- 10 requests come in at 15th second, the sliding window takes the timestamps and adds them into the log, allowing requests to go through

- 5 requests come in at 24th second. The sliding window takes the timestamps and adds them into the log. Then, it sees the log is over the threshold.

- When it compares, it finds out all 5 requests are over the threshold, and returns 429

- 10 requests come in at the 26th second. The sliding window sees that in the last 20 seconds, only 15 requests happened (the first bullet point is no longer kept)

- Note that the 5 rejected requests from previous point are present in the log, even though they were rejected

- It adds 5 requests, then notices the next 5 are over the threshold, and returns 429. But it still keeps them in memory

So, this is a little complex.

- It’s very effective. The rate limiting is very accurate. It will not allow through more requests than threshold within a set window.

- However, it’s not very memory efficient, because we keep the timestamps in memory - even if they are rejected.

Sliding Window Counter

So, previously, we’ve taken a look at some exact window measurement. What we’ll do now is very similar. We will try to combine the sliding window log with fixed time window. To do that, we’ll use the power of math! And also approximation.

Consider the following example:

- The window size is 1 minute, and the maximum amount of requests per minute is 10.

- We count the requests per time window, and have our own “rolling window” over it

- There have been 8 requests in the first minute

- We are 20 seconds into the second minute

- There have been 6 requests in the second minute so far

- That means the rolling window is between 00:20 to 01:20.

- Or, that also means that we are 66 % in the first minute, and 33 % in the second minute!

- To get the amount of available requests, we’ll get 0.66 8 (requests from minute one) and 6 33 (requests from minute two)

- By this combination, we get that the amount of requests happening in the last minute is 7.26

- All requests are allowed through

- Now, at 01:40, we get 10 more requests

- 0.33 * 8 from the first window

- 0.66 * (6 + 10) from the second window

- The limit is 13.2

- The last 3 request (or 4, depending on usage - you can both round up and round down) are rejected.

This last algorithm is memory efficient because it does not store anything. It also allows for very little trafic spikes.

However, it is also not exact. We should use this only if we don’t care about the approximation.

High Level Architecture

So, the high level architecture is actually really simple. Let’s review the requirements:

Limit excessive requests accurately

Low latency

Little memory usage

High fault tolerance

Exception handling (clear reasoning to users)

Distributed rate limiting (shared across servers)

So, the first thing is low latency and little memory usage. The low latency immediately implies we don’t want to store things in database due to how slow disk reads are.

So, we’ll use a cache. Other than low latency, it also offers time-based expiration strategies, making it ideal for rate limiting.

Finally, we’ll go with middleware. That means:

- A client sends request to rate limiting middleware

- Middleware checks the cache and compares if limit is reached or not

- If not, it allows the request to go through

And that’s it! We have a basic architecture

Architecture Deep Dive

So, we have already tackled the low latency. Now, let’s see how we handle the excessive requests, and what we do with those that were dropped.

First, we want to set up some rate limiting rules. They are usually saved on disc. We can see an example of Lyft’s rate limiting on GitHub

Specifically, we can see some examples in the config.yaml files:

domain: mongo_cps

descriptors:

- key: database

value: users

rate_limit:

unit: second

requests_per_unit: 500

- key: database

value: default

rate_limit:

unit: second

requests_per_unit: 500So, what we can do is we can simply write code for these config files, which we tune depending on our use case. Furthermore, we can limit multiple domains easily with them.

Now, what do we do when someone exceeds the rate limit? Well, we’ve already discussed the HTTP Code 429. But, that’s just a code. How can we let the user know something more meaningful?

Well, there’s a convention of using Ratelimit headers, specifically:

X-Ratelimit-Remaining- The number of allowed requests to go through until the next windowX-Ratelimit-Limit- The total number of allowed requests in a windowX-Ratelimit-Retry-After- The number of seconds to wait until a request can be made again without being throttled

By using these headers, we can then easily show a user some meaningful message, such as “Sorry, you’ve reached the amount of request, try again in X minutes”.

So, let’s review the things we need to do and see how we would deal with them:

Limit excessive requests accurately

~~Low latency~~ - We use cache rather than DB

~~Little memory usage~~ - We use cache rather than DB

High fault tolerance

~~Exception handling~~ - We return proper headers

Distributed rate limiting (shared across servers)

So, let’s continue with the first one. Since we are using Redis (which efficiently keeps timestamps), we can fairly easily solve this - What algorithm is the most exact and also happens to be using timestamps? That’s right, sliding window log! Another thing to tick off our list!

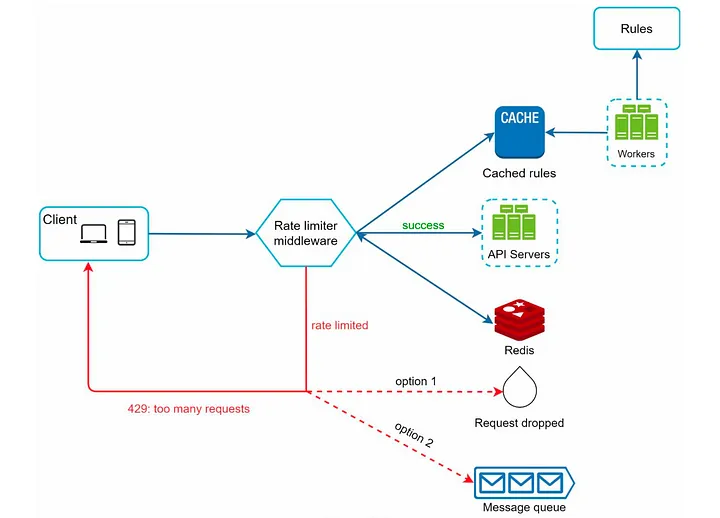

Now, before we continue with fault tolerance and distributed rate limiting, let’s revisit what we have in graph:

Above we can see what we have right now:

- We have a rate limiter middleware that passes requests to the web servers if the threshold is met

- The threshold and other rules are defined on a disk as rules in a

yamlfile. These rules are loaded into cache at regular intervals by workers. - If they are limited, the request is dropped

- Now, in the design, we have a message queue. There are patterns where requests do not immediately return 429, but there’s a threshold allowed for queueing requests.

- We can combine the two and define a threshold of say, 1500 requests to be added to the queue and handled at a later time, while all above that will be rejeced with 429

- If a request returns with 429, we send enough information to allow client to know why that is.

Distributed environment

Now, we have 2 last issues to tackle - distributed environment and high fault tolerance.

Having a rate limiter on a single server is easy, and we could just stop here, but distributed environment is challenging and will change our approach to high fault tolerance.

So, what are the main issues? Well, as is always the case with distributed environment:

- Race conditions

- If one user sends request before the second one, depending on the location, he might be disallowed

- Synchronization

- Multiple locations and millions of users imply multiple rate limiters. How would we share the cache?

So, let’s start with race conditions:

Consider the following example:

- Counter value in Redis is 3, and we allow 4 requests

- If two requests hit at the same time, both check if

currentValue + 1is less or equal to maximum. In this case, both requests would be accepted, because they both asume that the value is 4. However, in reality, it is 5.

Locking the requests while the cache is being manipulated is the most obvious solution. However, this may significantly slow down the system. Other than locks, we can write a script around saving the values into redis, or we can use a sorted sets with Redis

Now, for the synchronization issue:

- Similarly to DBs especially, having multiple servers can trigger issues

- If one server received requests from a client, and then another server received request from the same client, we have no idea how many times the client hit the server

- Sticky sessions can be used to share data from the client. However, that is not very scalable as we want components to be as separate as possible, and this effectively forces a bond between server and client

- A better way is to use a centralized data store for the rate limiters

- This way, multiple servers will use the same store

So, regarding the distributed environment - we’ve identified 2 main issues. Synchronization and race conditions. In this case, we’ve:

- chosen shared data source for synchronization

- chosen a sorted set data structure for race conditions

(We didn’t really choose them, but hey, at least we have an answer!)

Finally, the last part is high fault tolerance. To deal with that, I opt to avoid it as much as possible. We can do that by 2 things:

- Performance optimization - using cloudflare or another edge servers provider to have them near the client, and synchronize the data

- Monitoring - Once we’ve put it in place, we have worked on assumptions. However, reality may be different. We want to view the real data and see how effective it is, and, if necessary, change the rate limiting algorithm or rules.

Summary

So, in this part, we’ve dealt with thinking how to design a rate limiter, and we’ve answered some questions. For our use case:

~~Limit excessive requests accurately~~ - We used a proper algorithm. In our case, sliding window log was useful

~~Low latency~~ - We use cache rather than DB (redis)

~~Little memory usage~~ - We use cache rather than DB (redis)

~~High fault tolerance~~ - We optimize performance and monitor properly so that we can adjust the system

~~Exception handling~~ - We return proper headers upon which the client can act upon

~~Distributed rate limiting~~ - We've defined a strategy for race conditions (sorted sets) and for synchronization (shared data source)

Other than system design itself, we’ve gone through a couple algorithms - 5 of them to be exact.

Some final thoughts to be taken from here:

- Hard vs soft rate limiting

- Soft: Allow bursts of traffic (e.g. token bucket, fixed window counter)

- Hard: Disallow burst (e.g. leaking bucket, sliding window log)

- Rate limiting can be performed on different layers. Here, we’ve covered HTTP rate limiting, but we can limit on different places

- Try to avoid being rate limited on client implementation

- Cache to avoid making frequent calls

- Try to understand the limit and don’t send many requests in short time frame

- Do proper error handling

- Allow retry logic

- You can also try to add disallowed requests to a queue.

References