System Design 10 - Chat Service

Build our own discord

Introduction

Oh hello again! Nice to see you come by!

So far, we’ve gone through a lot of stuff. But at the same time, we still have a lot to learn!

In the first chapters, I’ve mentioned that working with stateful requests is not scalable. But sometimes, you don’t have a good choice.

Now, I still stand by that point - stateful architecture is weird. But how would you create a chat service without one? How would we be able to receive info from backend if the backend can’t push anything to us?

Now, bear in mind this is different than notifications - those are using different tools than our own APP. SMS, email, all of these are something different than simply receiving messages from the server.

So, how would we create a chat system?

Requirements

We have quite a bunch of different chat apps. Furthermore, we have a bunch of different types of chats! Consider the following:

- A facebook messenger where you chat 1-to-1 with your friend

- A discord chat room where you chat N-M with a lot of other people

- A combination of rooms & direct messages

So, to know how to approach something, what are the requirements for this app? Let’s assume the following:

- 1-to-1 and group chat

- mobile & web app

- 50 millions daily active users

- online indicator is available

- Message has a size limit of 100 000 characters

- End to end encryption is supported

- The chat history should be stored forever

So, those are our requirements.

High level design

So, what are the basics for a high level design?

Well, basically:

- The sender sends a message

- Chat service handles it, saves to database

- Chat service pushes the message to receiver

Now, in here, we’ll explore another network protocol. So far, we’ve been working with HTTP.

However, if we’d read the definition more closely:

A typical flow over HTTP involves a client machine making a request to a server, which then sends a response message

Now, that’s important! A client requests to a server! We don’t want that with a chat application.

Or we might! If we’d want that, we’d could go with polling

- Short polling is asking often

- Long polling is asking less often

Now, those are very vague descriptions. Let me quote the SO post:

Short polling:

00:00:00 C-> Is the cake ready?

00:00:01 S-> No, wait.

00:00:01 C-> Is the cake ready?

00:00:02 S-> No, wait.

00:00:02 C-> Is the cake ready?

00:00:03 S-> Yes. Have some lad.

00:00:03 C-> Is the other cake ready? ..Long polling:

12:00 00:00:00 C-> Is the cake ready?

12:00 00:00:03 S-> Yes.Have some lad.

12:00 00:00:03 C-> Is the cake ready? Specifically, note the timestamps.

But, let’s say we don’t want to use polling. Well, with HTTP, we have no other reasonable way to create a chat. In come WebSockets.

Now, with websockets, or ws for short, where only the initial call is HTTP, but all other ws calls are actually messages using a persistent connection. SignalR or Socket.IO are popular adopters.

So, we can finally consider our system:

- We’ll have a user

- We have a lot of users -> Multiple servers -> Load balancer

- We want to have users. Therefore, we also want authentication

- We will have some services working purely on HTTP

- Finally, we will have a chat service

- Connects to users as well

- Is stateful, imn contrast to other ones

- Finally, push notifications will be tackled by third party tooling.

Now, since there is no heavy lifting done on the regular servers, we COULD fit them all into one server. However, as was mentioned multiple times, single server means single point of failure. Therefore, as always, we’ll put them behind a load balancer.

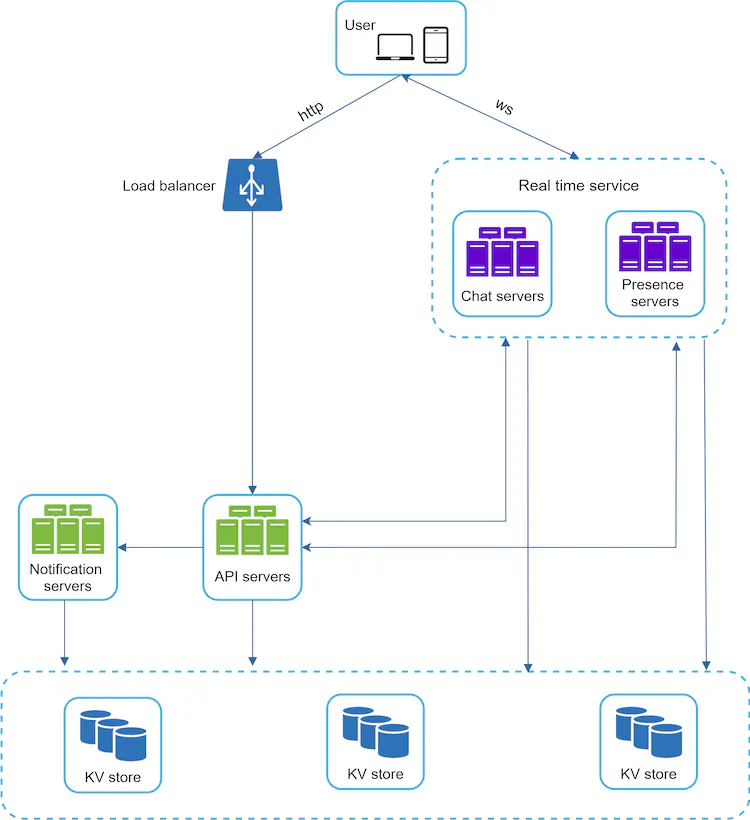

Now, finally, it could look something like this:

- We’ll have notification that handles PN to users, which will be triggered by API servers

- We’ll have API servers that handle authentication and initial services

- Finally, we’ll have real time service that contains the chat servers, as well as online presence.

All the data will be stored in key-value stores, as they are very solid choice for massive amounts of data.

Let’s hang with storage a little longer though. We’ve mentioned a lot of daily active users. Furthermore, we want it to be stored forever. Now, that’s a long time, isn’t it?

Well, let’s look at statistics. Messenger and WhatsApp process 60 billions messages per day. That’s A LOT. Imagine that you’re saving unicode characters (2 bytes in size) with that.

- 60 billions ~= 60 GB * 2 ~= 120 GB storage daily per character

- If the characters can be 100k chars long, that’d be 120 * 100.000 ~= 12 petabytes

Now, of course, we’ve all used messages. We can easily send twenty 3-char messages per minute. But it’s a lot of space.

So, all in all, we have to account for A LOT of storage space. How would we do that?

Well, again, we need to know how the data will be handled. Looking at how I recently worked with chats:

- Older messages are very rarely read, BUT we must support searching in history

- In general, we must support multiple searches - mentions, jumping to specific messages, …

- Read to write ratio is around 1:1

Because of that, key value stores are a really solid choice!

- Easy to scale horizontally

- Low latency to access data

- Popular chats use these

So, finally, the data model could look something like:

{

message_id: "number";

message_from: "number";

message_to: "number";

content: "string";

created_at: "timestamp";

}Now, in designing a unique ID generator, we’d probably reuse that. However, there can be quite a lot of messages created at one time with chats. Therefore, we’ll have ID that also works as sequence number.

With group messages, it’d be pretty much the same. The main difference here would be message_to being a channel ID. It would look something like:

{

message_id: "number";

user_id: "number";

channel_id: "number";

content: "string";

created_at: "timestamp";

}Finally, how’d the message ID look like?

I’ve mentioned multiple times that autoIncrement is insufficient because of scaling. However, this is a very specific case where it actually may be good enough! Kind of. Key value stores dont have autoincrement.

So, we’d use a local unique ID generation. Which could work very similar - we’d just have to generate it ourselves. Now, why would it work here?

Because users are already part of some channels. So the IDs need to be unique only within the context of the data. If you have a message between

user A and user B, then if the id clashes with a message between user B and user C, it’s not an issue. You can still identify it!

Nonetheless, it is still possible to create our own unique distributed ID for this as well.

Deep dive

So, we’ve established how our storage works, what’s being used, how chats work. Now, one of the things I mentioned is that we are using websockets to connect to chat server. However, WHAT chat server? Remember, there will probably be a lot of them.

So, how would we connect 2 users to a specific server? Well, we’ll have to use what’s called a Service Discovery.

Apache ZooKeeper is a popular open source that we can use. From description:

ZooKeeper is a centralized service for maintaining configuration information, naming, providing distributed synchronization, and providing group services

The flow would then look like:

- A user logs into the app

- Load balancer forwards it to API servers

- API server does authentication and other thingies, then finds the best chat service

- The chat service to be used is returned to user, and user finally connects to specific server through websocket.

Direct messages

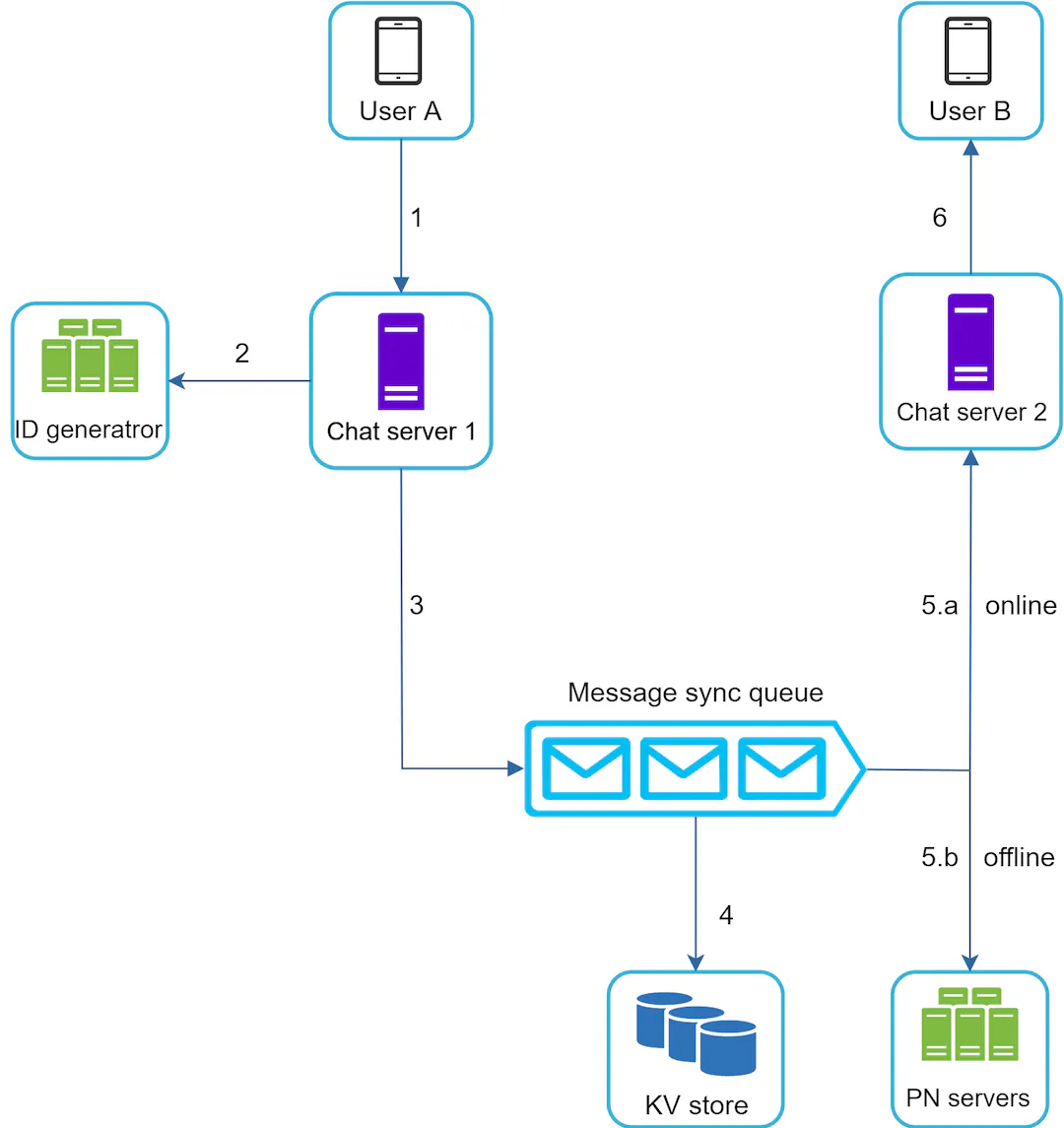

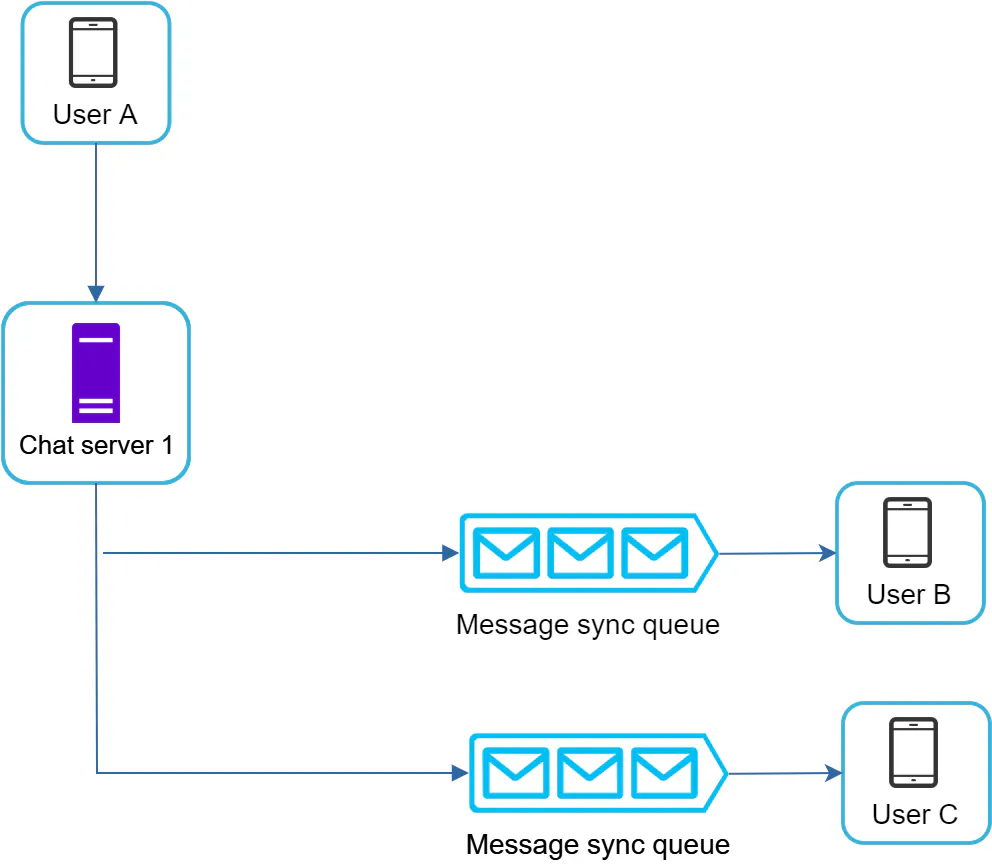

So, provided that user is already on the chat server, the following happens:

- user A sends a chat message to chat server 1

- chat server 1 obtains the message ID from generator and adds it to a message queue

- Message queue stores it into key-value store and forward it to:

- If user is online, the message is forwarded to server where user B is connected

- server forwards the message to user B through WebSocket

- If user is offline, the message is sent as a notification. On next app load, the user will fetch it with other messages

- If user is online, the message is forwarded to server where user B is connected

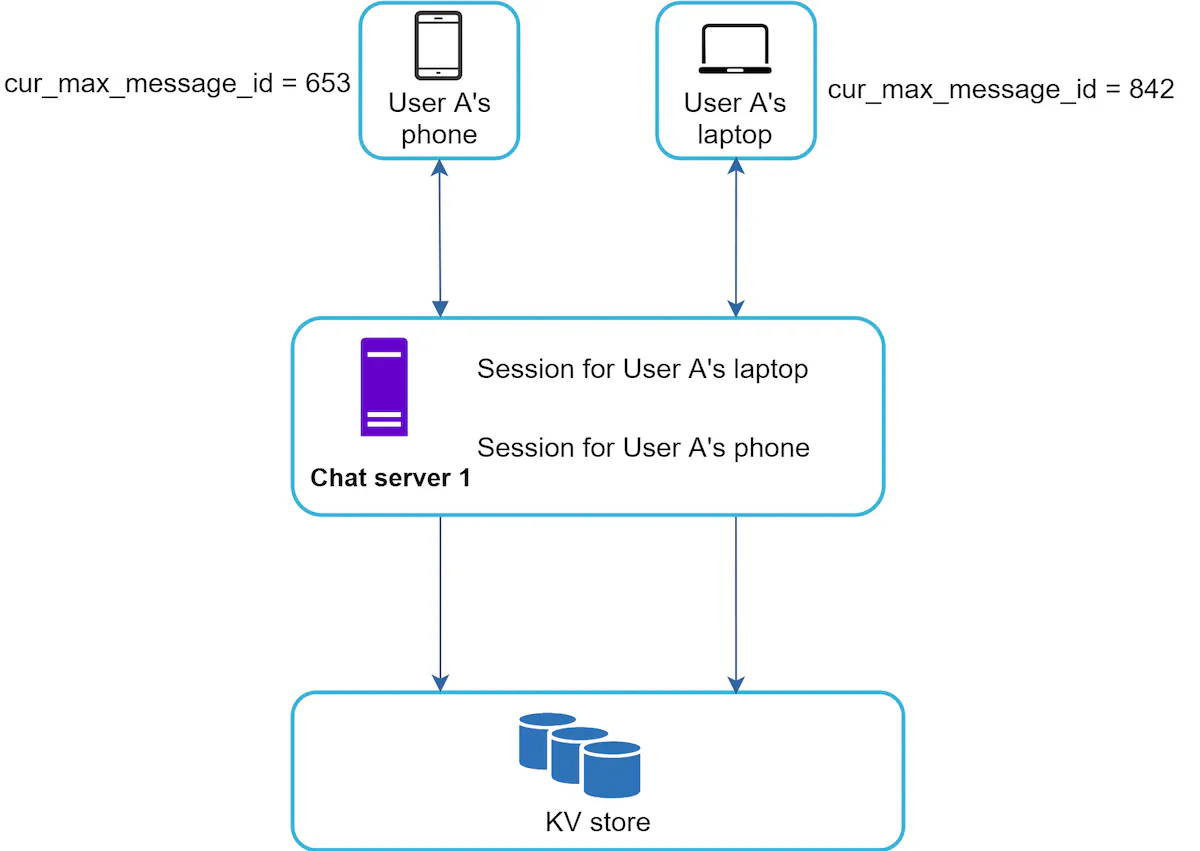

Now, the potential problem here is synchronization between multiple devices. Imagine you’re on Facebook and you’re logged on your desktop and mobile simultaneously.

To achieve some synchronization in here. we might keep track of latest message ID. How’d that work?

Well, we’d have something like:

- The message is sent to a recipient, who is always the

user_id - The client will keep track of

last_message_id - If

last_message_idis lower than new message in KV store, then new messages are fetched

Group chats

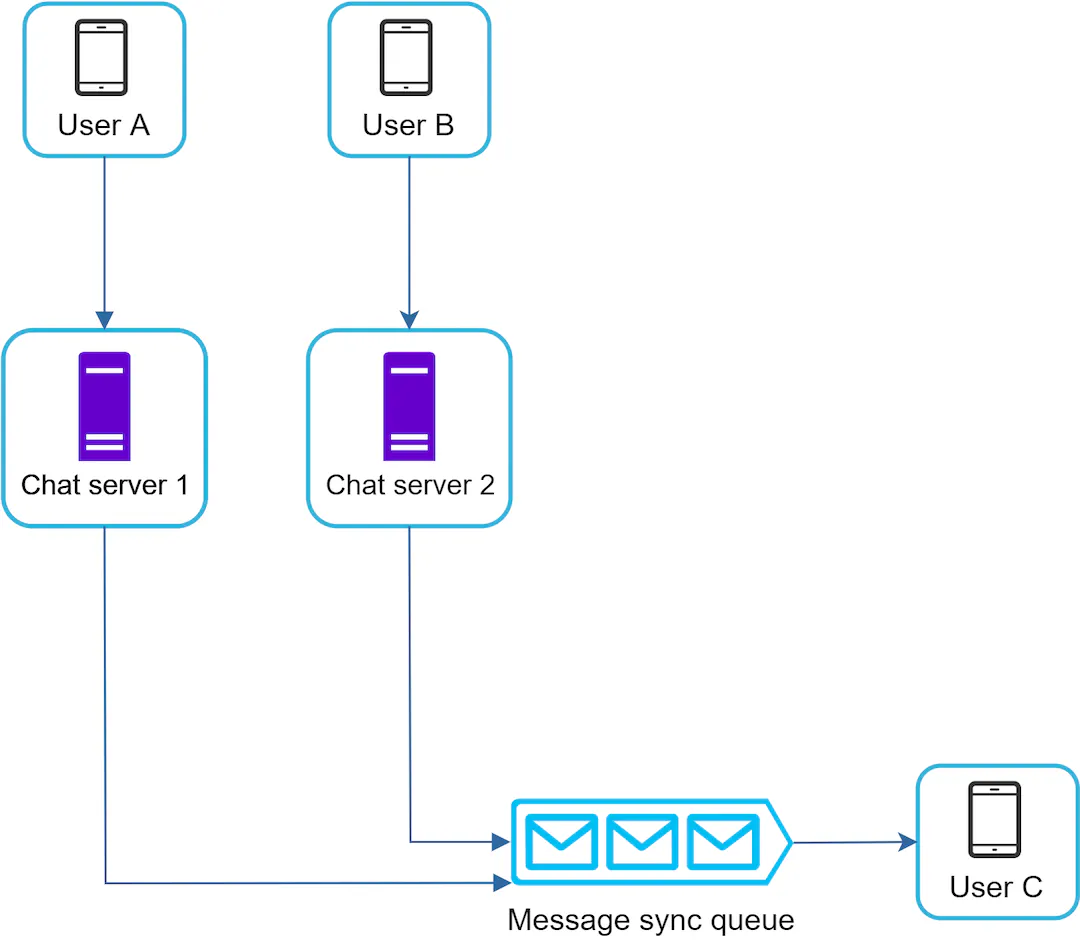

Group chats are a little more complicated. We can view them as direct messages, except the message is sent to multiple users. So how would that work?

Well, first, we need to understand that when we sent a message, we basically send it to multiple users. So, we could take the design from before

Consider the previous design. What do we need to add a user? Well, we’ll just another link from message queue to another chat server.

We could do that, and that would work. However, if we want to be a little more scalable, we could add more message queues. We could have a message queue for each user connected to the chat server

That’d be beneficial for two reasons:

- When messages are outgoing, they will go one by one to the end user

- When the messages are incoming (read: I logged in and have 20 different messages from multiple people), then I’d just load my own messages easier

So, the final flow could be like:

sending messages

receiving messages

Online presence

Now, the last problem we need to deal with is online presence. An indicator is often shown - a green dot if a user is online, for example.

How would that work? Well, let’s first think about how we could do that.

- We need to keep track if user is online or not

- Client sends heartbeat requests to server every N seconds

- If a client did not respond for M seconds, he is considered offline

- When users logs out or logs in, he’d start or stop sending the requests, solving that as well.

- When user disconnects because of connection termination, these requests don’t happen, so it works for this.

So, that’s a lot of requests. To not slow down our regular servers, let’s have some Presence services.

Finally, users would be subscribed to message queues on these servers, depending on whether those are group chats or not

Summary

So, here we are again! At the end of the road for chat service. Let’s look at what we’ve learned and how we’ve designed it. Going back:

- 1-to-1 and group chat

- mobile & web app

- 50 millions daily active users

- online indicator is available

- Message has a size limit of 100 000 characters

- End to end encryption is supported

- The chat history should be stored forever

So, how did we do?

- The 1-to-1 and group chat designs were created

- Mobile & Web app were tackled with synchronization

- 50 millions DAU are handled by multiple servers, KV stores and websockets

- Online indicator via heartbeat

- Message limit is basically storage limit - We’ve used suitable storage component

- Chat history should be stored forever -> KV stores are easily scaled horizontally

- End to End encryption was not discussed

So, we are missing one thing. So let’s have a quick look at that!

End to end encryption basically means - we as a provider can’t read messages. So, what would happen is we basically need to encrypt the data:

- Private and Public key of each user

- Public keys are stored on server to hash the message

- Private keys are used on client to decrypt the message

Now, with group chats, that’s a little more complicated. We have a lot of options.

One we could use is just PGP. The gist of it is:

- Generate a key and use it to hash text

- Hash this key using public key of recipients

- Send hashed key to recipients

- Each client would then first decrypt the hashed key

- Then with decrypted key, he’d decrypt his message

- Finally, he can read the message

And that’s it! We’ve created a chat system!

References