Graphs

Social networks & stuff

Introduction

So, we’re getting to the end of this part. Graphs are the last piece of data structures I’ll investigate as part of this series.

So, what are graphs? Well, graphs are a form or trees. But not really.

They are really similar - we have nodes that are connected. As such, all trees are graphs.

But not all graphs are trees. Graph is a big thing in mathematics - Graph Theory is a big concept, and there’s a lot of terminology to be used:

- an edge is a connection between two graphs

- a vertex is a node in a graph

- a vertex can have 0 to N neighbors (or adjacent vertices) connected by an edge.

- we can have multiple types of graphs

- directed graph - vertices are linked asymmetrically (one-way)

- undirected graph - vertices are linked symmetrically (two-way)

- weighted graph - edges have “a price” - some paths have a value

- unweighted - there is no value

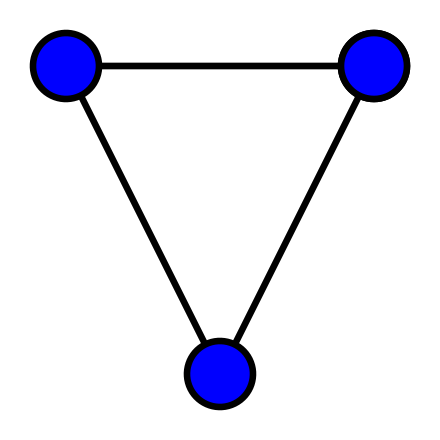

An undirected graph is one that has vertices and nodes, but no path is forced. An example is cities and roads leading to them on the map.

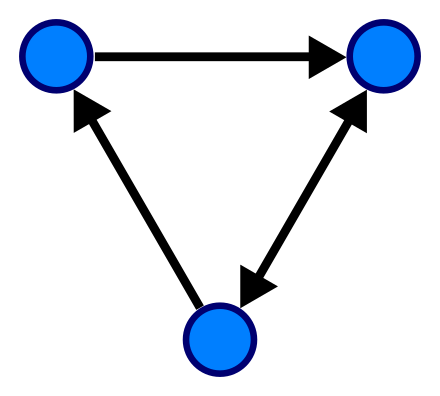

A directed graph, on the other hand, is one that has a forced path. Example of this can be social network (I’m following you, you’re not following me).

Finally, each of them can be either weighted or unweighted. The cities and roads leading to them exist, but some roads are longer than others and take more time. That’s the example of weighted graph

Finally, an unweighted graph has no value along the edge.

If you think about it, a 2D array can also be viewed as a graph in some cases:

const arr = [

[1,2,3],

[4,5,6],

[7,8,9],

]Consider that you have this array and you want to find a cheapest way from top right to bottom left.

- You start in one vertex (1)

- You have values in the individual nodes

- When you move to a next node, you carry the “price” for moving there

Graphs are all around us and a lot of things can be described by graphs. They are very important, and the most successful products (= social networks) use them extensively.

One thing to note that all the data structures we’ve gone through can be stored in databases made for those specific use cases. There are some databases to store graphs especially:

- Neo4J

- ArangoDB

- Giraph Apache

- …and definitely more

Scope

Since there are quite a few graphs, I’d like to do a couple things here.

- I’ll create a couple graphs - weighted and unweighted

- I’ll apply 3 algorithms

- Breadth-First search

- Depth-First search

- Dijkstra

Finally, I’ll apply all of these on some other concepts (trees, arrays, objects).

Directed and Undirected graphs

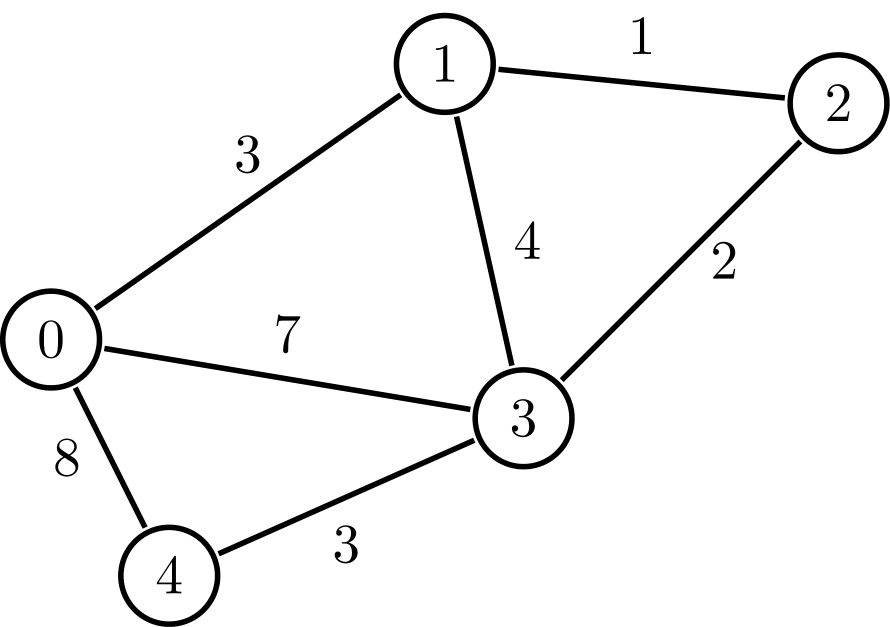

Let’s start with directed and undirected graphs, because it’s fairly straightforward. Look at the images above:

- A directed graph is one-way

- An undirected graph is two-way

Well, that’s nice. But how do we achieve it? Let’s create a vertex for that:

class Vertex {

value;

adjacentVertices;

constructor(value) {

this.value = value;

this.adjacentVertices = [];

}

}In the vertex above, we have:

- value - a node holds any value

- adjacent vertices (or neighbors) - connected nodes

Notice that we don’t have a class called “Graph”. Only individual nodes. So to connect them, we just add links within the array

- With directed vertex, we only add vertex to the current node

- With undirected vertex

- we add adjacent vertex to the current list

- we add the current vertex to the neighbor list

So, let’s do that real quick and define both directed and undirected vertices:

class DirectedVertex extends Vertex {

constructor(value) {

super(value);

}

addAdjacentVertex(vertex) {

this.adjacentVertices.push(vertex);

}

}

class UndirectedVertex extends Vertex {

constructor(value) {

super(value);

}

addAdjacentVertex(vertex) {

if (this.adjacentVertices.includes(vertex)) return;

this.adjacentVertices.push(vertex);

vertex.addAdjacentVertex(this);

}

}And that’s actually all for directed and undirected graphs! The weighted will be pretty much the same, just with different weight! But we’ll see that later.

Unweighted Graphs

So, with the code above, we have all we need for creating unweighted graphs, because there is no weight taken into account whatsoever!

Now, you don’t actually need to use classes for that. It’s just easier. You might as well have a simple object to do the same thing:

const friends = {

"Bob": ["Cynthia"]

"Cynthia": ["Bob"],

"Elise": ["Fred"],

"Fred": ["Elise"]

}That is actually a undirected graph. Let’s look closer:

- Bob is friend with Cynthia and Elise is friends with Fred

- The “friends” is basically two-way, making it undirected

Now, let’s make this directed - let’s look at followers!

const followees = {

"Bob": ["Cynthia"],

"Cynthia": ["Bob", "Fred", "Elise"],

"Elise": ["Fred"],

"Fred": ["Elise"]

}While friends was always 1-1 relationship, in here, we can potentially have 1-0 (as in individual links).

The reason I used classes above is to have an easier access to adding the vertices. But, for the sake of recap, let’s do it in objects as well:

const followees2 = {

Bob: {

follows: ["Cynthia"],

addFollower(follower) {

this.follows.push(follower);

},

follow(who) {

followees2[who].addFollower();

},

},

Cynthia: {

follows: ["Bob"],

addFollower(follower) {

this.follows.push(follower);

},

follow(who) {

followees2[who].addFollower();

},

},

};You can see that both function addFollower and follow are identical. We could use a factory pattern in here. Or classes. But the idea is the same as

with classes above.

In any way, no matter the direction, we could still potentially get to the same node. Consider the following:

const friends = {

"Bob": ["Cynthia"],

"Cynthia": ["Bob"],

}

const followees = {

"Bob": ["Cynthia"],

"Cynthia": ["Daniel"],

"Daniel": ["Bob"]

}While the first object is undirected, the second object is directed. In both cases, we can get to the original node. This is why some graphs are not trees - they can be circular.

And that’s the main problem we’ll be tackling here with algorithms. What we need to solve is basically:

- Go through all vertices (or traverse, if you will)

- Make sure that visited vertices won’t be taken twice

For weighted graphs, there’s another rule, But we’ll leave that for later. Without further ado, let’s get started with Depth-first search!

DFS

Depth-first search is an algorithm for traversing graphs (and by extension, trees).

The idea is:

- Go to the deepest node first there is (depth)

- From there, go back up and continue

This applies to graphs as much as it applies to trees. But for the sake of simplicity, I’ll describe the example with trees. Consider the following tree:

- 1

- 2

- 4

- 5

- 3

- 6

- 7

- 2

If we perform binary search on the tree above, we’ll visit the nodes in order 1, 2, 4, 5, 3, 6, 7. That is:

- Go to the leaf level (1, 2, 4)

- Go to next leaf (5)

- Go to next leaf level in different branch (3, 6)

- Go to next leaf (7)

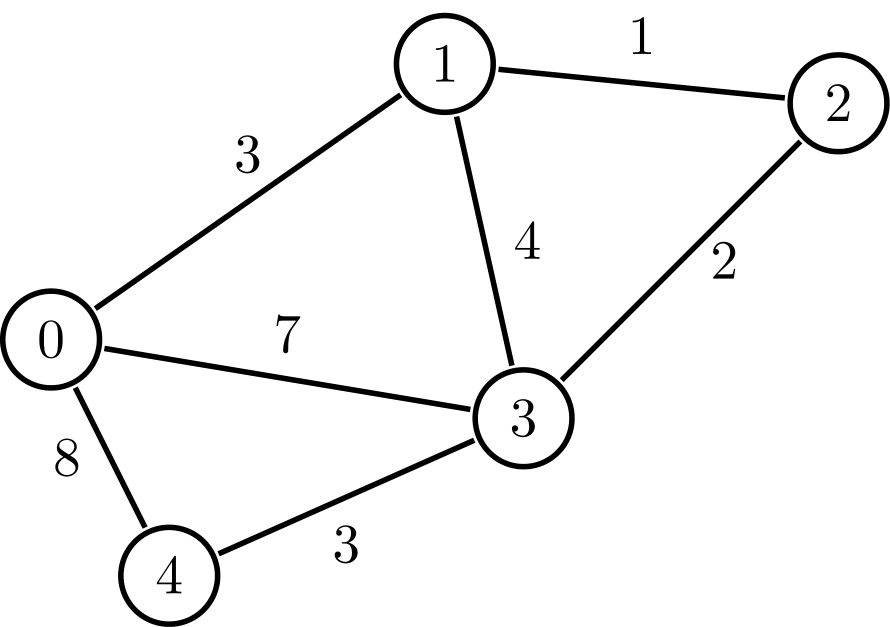

Now, this works for charts as well - we’ll go to the furthest connected link and then go back up. Let’s use the weighted example from above:

Now, there are weights here, but let’s just ignore them here because I’m to lazy to steal another image from wikipedia, and focus at the nodes. In this case, DFS will be as follows:

- Starting from node zero, we’ll traverse to the left node always:

- We go through

0, 1, 2, 3, 4 - Now, we could continue to

0. But that’d be circular! So, we won’t visit0again!

Note: The left node I mentioned above is not the rule. You COULD apply it, but more often than not, you’ll likely just go through whatever is first in the array of links.

And another note - the algorithm is called search. That’s because it’s often used to find a value and return it.

If you’d search for node 2, you would do an early return and not search through the entire graph

That being said, you can use it for traversing the entire graph.

To perform the search, I’ll use the code below to created vertices with the object-oriented way:

const alice = new UndirectedVertex("Alice");

const candy = new UndirectedVertex("Candy");

const bob = new UndirectedVertex("Bob");

const fred = new UndirectedVertex("Fred");

const helen = new UndirectedVertex("Helen");

const derek = new UndirectedVertex("Derek");

const elaine = new UndirectedVertex("Elaine");

const gina = new UndirectedVertex("Gina");

const irena = new UndirectedVertex("Irena");

alice.addAdjacentVertex(bob);

alice.addAdjacentVertex(candy);

bob.addAdjacentVertex(fred);

fred.addAdjacentVertex(helen);

candy.addAdjacentVertex(helen);

alice.addAdjacentVertex(derek);

alice.addAdjacentVertex(elaine);

derek.addAdjacentVertex(elaine);

derek.addAdjacentVertex(gina);

gina.addAdjacentVertex(irena);The code looks as follows:

const depthFirstSearch = (current, visited = {}) => {

console.log(current.value)

visited[current.value] = true;

current.adjacentVertices.forEach(adjacent => {

if (visited[adjacent.value]) return;

visited[adjacent.value] = true;

depthFirstSearch(adjacent, visited)

});

}

depthFirstSearch(alice)With the above code, we’ll get the following logs: ‘Alice’ -> ‘Bob’ -> ‘Fred’ -> ‘Helen’ -> ‘Candy’ -> ‘Derek’ -> ‘Elaine’ -> ‘Gina’ -> ‘Irena’

If we look at the way how vertices were created, it becomes clear:

- We’ve first added friends to ‘Alice’ - ‘Bob’ and ‘Candy’

- Then we added friends to ‘Bob’ - ‘Fred’

- Then we friends to ‘Fred’ - ‘Helen’

- Then we added friends to ‘Candy’ - ‘Helen’

Now, I could go on and on, but we already have what we need

- Alice friended Bob first, who is friends with Fred, who is Friends with Helen

- Because of this “depth”, those are the first ones logged

- Then, it continues from ‘Candy’ - because that’s another link

So, now that this is clear, let’s get to the “search” part:

- We just add an if to the beginning of the function

So, the final search could be:

const depthFirstSearch = (current, searchFor, visited = {}) => {

if (current.value === searchFor) return current;

visited[current.value] = true;

for (let i = 0; i < current.adjacentVertices.length; i++) {

const adjacent = current.adjacentVertices[i]

if (visited[adjacent.value]) continue;

visited[adjacent.value] = true;

const found = depthFirstSearch(adjacent, searchFor, visited)

if (found) return found;

}

return null;

}

depthFirstSearch(alice, "Fred")I’ve made to things here:

- I’ve changed the

forEachtoforbecause you can’t do an early return fromforEach - I’ve added check to the start

If we’d log the individual nodes, we’d get “Alice” -> “Bob” -> “Fred” and just return early.

And that’s it for depth-first search! We’ve just managed to create one using recursion! Onto BFS!

BFS

Breadth-first Search is very similar to DFS, and use I’ll exactly the same code here for the setup.

Now, using the same examples, let’s see what happens when we go through the following tree with BFS:

- 1

- 2

- 4

- 5

- 3

- 6

- 7

- 2

With DFS, we’ve gone through it in order 1, 2, 4, 5, 3, 6, 7.

With BFS, the order would be 1,2,3,4,5,6,7. The reason for that is that we’re moving per level (breadth), rather than going deep first.

Now, using the same vertices as before, let’s write BFS for the same setup. The following code is copied from above:

const alice = new UndirectedVertex("Alice");

const candy = new UndirectedVertex("Candy");

const bob = new UndirectedVertex("Bob");

const fred = new UndirectedVertex("Fred");

const helen = new UndirectedVertex("Helen");

const derek = new UndirectedVertex("Derek");

const elaine = new UndirectedVertex("Elaine");

const gina = new UndirectedVertex("Gina");

const irena = new UndirectedVertex("Irena");

alice.addAdjacentVertex(bob);

alice.addAdjacentVertex(candy);

bob.addAdjacentVertex(fred);

fred.addAdjacentVertex(helen);

candy.addAdjacentVertex(helen);

alice.addAdjacentVertex(derek);

alice.addAdjacentVertex(elaine);

derek.addAdjacentVertex(elaine);

derek.addAdjacentVertex(gina);

gina.addAdjacentVertex(irena);Now, for the breadth first search, since we’re moving by levels, we’ll do the following:

- We define an initial node

- We keep track of visited nodes

- We’ll create a queue and add the initial node to it

- We get the first item in the queue and remove it from the queue

- For each sibling, we add it to the queue if it was not already visited

- We print the item

- We perform the last 3 steps until the queue is empty

Finally, it’ll look liker this:

const breadthFirstSearch = (initialNode) => {

const visited = {};

const queue = [initialNode];

visited[initialNode.value] = true

while (queue.length > 0) {

const current = queue.shift();

current.adjacentVertices.forEach(vertex => {

if (!visited[vertex.value]) {

queue.push(vertex)

}

visited[vertex.value] = true

});

}

}

breadthFirstSearch(alice)Note the positions of the visited definitions:

- We define initial node as visited at start for the first node because it’s already in the queue

- We define each node as visited the moment we add it to queue

- If we only added the visited flag inside the loop, we could get some nodes twice (e.g. multiple “2nd level” siblings could be friends with same “3rd level” sibling)

Now, if we look at the initilization, we’ve started on node ‘Alice’.

- ‘Alice’ has 4 links - Bob, Candy, Derek, Elaine.

- ‘Bob’ has 1 link - Fred

- ‘Candy’ has 1 link - Helen

If we put a print call on the current node in the while function, we’ll see the following order:

Alice -> Bob -> Candy -> Derek -> Elaine -> Fred -> Helen -> Gina -> Irena

So, we can easily see that we are going by sibling nodes. And finally, if we wanted to search for a value, we’d just early return it within the while loop

DFS vs BFS

After writing the code for both, let’s compare them now! For the following setup:

const alice = new UndirectedVertex("Alice");

const candy = new UndirectedVertex("Candy");

const bob = new UndirectedVertex("Bob");

const fred = new UndirectedVertex("Fred");

const helen = new UndirectedVertex("Helen");

const derek = new UndirectedVertex("Derek");

const elaine = new UndirectedVertex("Elaine");

const gina = new UndirectedVertex("Gina");

const irena = new UndirectedVertex("Irena");

alice.addAdjacentVertex(bob);

alice.addAdjacentVertex(candy);

bob.addAdjacentVertex(fred);

fred.addAdjacentVertex(helen);

candy.addAdjacentVertex(helen);

alice.addAdjacentVertex(derek);

alice.addAdjacentVertex(elaine);

derek.addAdjacentVertex(elaine);

derek.addAdjacentVertex(gina);

gina.addAdjacentVertex(irena);We’ve the following prints:

- DFS:

Alice -> Bob -> Fred -> Helen -> Candy -> Derek -> Elaine -> Gina -> Irena - BFS:

Alice -> Bob -> Candy -> Derek -> Elaine -> Fred -> Helen -> Gina -> Irena

With both, we need to traverse the entire graph if we’re using it for traversal, and it’s O(N).

However, if we were searching for a value, it might be different. Consider searching for “Fred” and “Candy” in the above example:

- Fred - DFS in 3 steps, BFS in 6 steps

- Candy - DFS in 5 steps, BFS in 3 steps

Depending on the structure of your graph, you may want to use different searching algorithm.

Weighted Graphs

Now that we’ve gone through unweighted graphs, let’s look at weighted graphs. Before going into detail of them, there are basically 2 differences:

- Weighted graphs are always directed (kind of)

- We need to keep track of weight

So, looking at the above, let’s create a class again:

class Vertex {

name;

adjacentVertices;

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

this.adjacentVertices = new Map();

}

}

class WeightedVertex extends Vertex {

constructor(name) {

super(name);

}

// Adjacency list

addAdjacentVertex(vertex, weight) {

this.adjacentVertices.set(vertex, weight);

}

}Now, we can see 2 things here:

- Vertices links are maps, not arrays

- When adding, we are setting to the map

Now, why did I say that weighted graphs are always directed? Well, directed doesn’t strictly mean one-way. In unweighted, it does, but with weighted ones:

- Consider taking a trip from London to Paris and back

- For whatever reason (e.g. road condition), while you have road from London to Paris and back, they may be different

- There may be some closures on the road

- There may be weather condition that make it impossible to go on one of the roads

- Basically, even though you connect London to Paris, you can have different weights

Both directions can have same value, sure. But it’s a weighted value that could potentially at some point change.

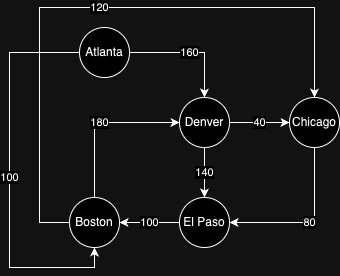

Again, as was the case in previous part, this is all we neded to create a bunch of vertices. Let’s do a couple here. I’ll use cities in this case rather than friends:

Now that we have it defined, let’s discuss a little more about the use cases. Because weighted basically means you want to follow some path. In other words, using weighted graphs is often used in pathfinding, and we’ll use pathfinding algorithms here. There’s quite a few of them

- Dijkstra

- A*

- And more (I can’t pretend I know all)

In this case, I’ll show Dijkstra’s algorithm.

const denver = new WeightedVertex("Denver");

const elPaso = new WeightedVertex("El Paso");

const chicago = new WeightedVertex("Chicago");

const boston = new WeightedVertex("Boston");

const atlanta = new WeightedVertex("Atlanta");

denver.addAdjacentVertex(elPaso, 140);

denver.addAdjacentVertex(chicago, 40);

chicago.addAdjacentVertex(elPaso, 80);

elPaso.addAdjacentVertex(boston, 100);

boston.addAdjacentVertex(chicago, 120);

boston.addAdjacentVertex(denver, 180);

atlanta.addAdjacentVertex(boston, 100);

atlanta.addAdjacentVertex(denver, 160);So, as mentioned above, let’s find to shortest path between some cities. To visualize it, I’ve attempted the following draw.io diagram:

Now, some things to see here. Consider the links from Denver

- From Denver to El Paso, the weight it 140

- From Denver to Chicago, it’s 40

- From Chicago to El Paso, it’s 80

Now, that’s important. Because if you’ll look closely, the shortest path from Denver to El Paso is not the direct link - it’s actually through Chicago!

So, let’s consider we want to go from denver to el paso. How’d we do that?

- From Denver to Denver, the cost is 0

- From Denver to El Paso, the cost is 140

- From Denver to Chicago, the cost is 40

- From Chicago to El Paso, the cost is 80

- We’ve already visited El Paso once! So, we’ll track back

- We know that previously, the value is 140

- Now, the value is 40 + 80

- We save the value

120as the cost to get from “Denver” to “El Paso”, following this path

Now, remember that back tracking part, because I’ll refer to it later.

So, how does Dijkstra work? Well, let’s look at it:

- As usual, we will start from any vertex, and we’ll be finding shortest path to another vertex

- We’ll compare the weights from the current vertex to adjacent ones

- As previously, we’ll use hash tables

- visited nodes

- cheapest cost (“Denver” to “El Paso” is 120, not “140”)

- previous stops (All the stops followed to get there)

- We’ll also keep a queue of unvisited nodes, same as we did with BFS, to keep it from running infinitely

function getCityStopsAndPriceList(startVertex) {

const cheapestCityToValue = {};

const previousStopsMap = {};

const queue = [startVertex];

const visited = {};

cheapestCityToValue[startVertex.name] = 0;

while (queue.length > 0) {

const current = queue.shift();

visited[current.name] = true;

/* There will be something here */

}

}For visiting the adjacent nodes, we’ll perform the following:

- We get adjacent vertices

- We iterate over the vertices

- If the vertex hasn’t been visited yet, we add it to the unvisited array

- Remember that we keep track of how much it costs to get somewhere? Here, we’ll actually use it

- We’ll retrieve the value how much it costs to get to the adjacent vertex

- If there is no value, we add the current value

- If the passing value is lesser than the existing value, we overwrite it

Now, that’s a little chaotic. So, let’s make it easier with a smaller example:

- We are in the node “Denver”. The cost to get from “Denver” to “Denver” is 0. We add it to the

cheapestCityToValuehash map - We go to node “El Paso”. The cost to get from “Denver” to “El Paso” is 140. We add it to the

cheapestCityToValuehash map - We go from “Denver” to “Chicago”. The cost is 40. We add it to the

cheapestCityToValuehash map - Now, we have a hash map of

{ Denver: 0, El Paso: 140, Chicago: 40 } - We go from “Chicago” to “El Paso”. The cost is 80.

- We’ve already visited “El Paso” with the cost of 140

- We compare the current path from the hash map -

Chicago: 40- and the current cost -80 - We see that

80 + 40is less than140 - We replace the

cheapestCityToValue

- We’ll now have a list of

{ Denver: 0, El Paso: 120, Chicago: 40 }

So, the passing value is basically the path to current node we’re at.

So, the code will do exactly that:

- Get adjacent vertices

- Iterate over them

- Add those that haven’t been visited to a queue

- Define the cost to these vertices by

- Initializing the value with passing value (cost to current city + link cost)

- Replace the hash map value if current value is lesser than already existing

function visitAdjacentVertices() {

const adjacentEntries = current.adjacentVertices.entries();

for (const [adjacentVertex, value] of adjacentEntries) {

if (!visited[adjacentVertex.name]) queue.push(adjacentVertex);

const passingValue = (cheapestCityToValue[current.name] || 0) + value;

const alreadyFoundValue = cheapestCityToValue[adjacentVertex.name];

const currentHasValue = alreadyFoundValue != null;

if (!currentHasValue || passingValue < alreadyFoundValue) {

cheapestCityToValue[adjacentVertex.name] = passingValue;

previousStopsMap[adjacentVertex.name] = current.name;

}

}

}We put it all together:

function dijkstra(startVertex) {

const cheapestCityToValue = {};

const previousStopsMap = {};

const queue = [startVertex];

const visited = {};

cheapestCityToValue[startVertex.name] = 0;

while (queue.length > 0) {

const current = queue.shift();

visited[current.name] = true;

const adjacentEntries = current.adjacentVertices.entries();

for (const [adjacentVertex, value] of adjacentEntries) {

if (!visited[adjacentVertex.name]) queue.push(adjacentVertex);

const passingValue = (cheapestCityToValue[current.name] || 0) + value;

const alreadyFoundValue = cheapestCityToValue[adjacentVertex.name];

const currentHasValue = alreadyFoundValue != null;

if (!currentHasValue || passingValue < alreadyFoundValue) {

cheapestCityToValue[adjacentVertex.name] = passingValue;

previousStopsMap[adjacentVertex.name] = current.name;

}

}

}

}Now, if you look at it, it’s not really returning any short path. And here comes the important bit. Let’s compare it to BFS algorithm:

const breadthFirstSearch = (initialNode) => {

const visited = {};

const queue = [initialNode];

visited[initialNode.value] = true

while (queue.length > 0) {

const current = queue.shift();

current.adjacentVertices.forEach(vertex => {

if (!visited[vertex.value]) {

queue.push(vertex)

}

visited[vertex.value] = true

});

}

}If you compare them, you’ll notice that what I’ve just described is BFS with a couple additions:

- We are using a queue for adjacent nodes

- We are adding to the queue only if it hasn’t yet been visited

So, the only change actually is:

- Keeping track of already visited cities

- “Looking forward” - When I’m in Chicago and I’m seeing El Paso, I don’t go INTO it. I updated the value based on the link

- I update everything relative to the node i’m starting at

And that’s it. The only thing we are doing is we are traversing the array. And now you could say “Hey, but there’s finding the path, is there?”

Well, you’re completely right. Because this algorithm uses BFS, but extends it. And also, it’s not really dijkstra yet.

At this point, we’ve found the value to go to any city. Let’s look what we get if we console log the cheapestCityToValue and previousStopsMap

console.log(cheapestCityToValue) // { Denver: 0, 'El Paso': 120, Chicago: 40, Boston: 240 }

console.log(previousStopsMap) // { 'El Paso': 'Chicago', Chicago: 'Denver', Boston: 'El Paso' }Now, you probably see what I meant when I mentioned the “Looking forward” - we have value to get to Boston, even though we never visited it. That’s a side effect of looking forward.

Anyways, now that we have all this data, we can find the shortest path!

- We have the destination and start

- We’ll enter the

previousStopsMapand backtrack from there- Start in ‘El Paso’

- Go to ‘Chicago’

- Go to ‘Denver’

- (compare that start is the same as current, break if true)

- We push this in an array and we have the path

El Paso, Chicago, Denver. We reverse the array and we have the path!

function shortestPath(startVertex, destination) {

const { cheapestCityToValue, previousStopsMap } = dijkstra(startVertex);

const shortestPath = [];

let currentCityName = destination;

while (currentCityName !== startVertex.name) {

shortestPath.push(currentCityName);

currentCityName = previousStopsMap[currentCityName];

}

shortestPath.push(currentCityName);

return {

path: shortestPath.reverse(),

price: cheapestCityToValue[destination],

};

}

function dijkstra(startVertex) {

const cheapestCityToValue = {};

const previousStopsMap = {};

const queue = [startVertex];

const visited = {};

cheapestCityToValue[startVertex.name] = 0;

while (queue.length > 0) {

const current = queue.shift();

visited[current.name] = true;

const adjacentEntries = current.adjacentVertices.entries();

for (const [adjacentVertex, value] of adjacentEntries) {

if (!visited[adjacentVertex.name]) queue.push(adjacentVertex);

const passingValue = (cheapestCityToValue[current.name] || 0) + value;

const alreadyFoundValue = cheapestCityToValue[adjacentVertex.name];

const currentHasValue = alreadyFoundValue != null;

if (!currentHasValue || passingValue < alreadyFoundValue) {

cheapestCityToValue[adjacentVertex.name] = passingValue;

previousStopsMap[adjacentVertex.name] = current.name;

}

}

}

}And we’ve successfully found a pathing through a chart!

Code

DFS:

const depthFirstSearch = (current, visited = {}) => {

console.log(current.value)

visited[current.value] = true;

current.adjacentVertices.forEach(adjacent => {

if (visited[adjacent.value]) return;

visited[adjacent.value] = true;

depthFirstSearch(adjacent, visited)

});

}BFS:

const breadthFirstSearch = (initialNode) => {

const visited = {};

const queue = [initialNode];

visited[initialNode.value] = true

while (queue.length > 0) {

const current = queue.shift();

current.adjacentVertices.forEach(vertex => {

if (!visited[vertex.value]) {

queue.push(vertex)

}

visited[vertex.value] = true

});

}

}Dijkstra:

function shortestPath(startVertex, destination) {

const { cheapestCityToValue, previousStopsMap } = dijkstra(startVertex);

const shortestPath = [];

let currentCityName = destination;

while (currentCityName !== startVertex.name) {

shortestPath.push(currentCityName);

currentCityName = previousStopsMap[currentCityName];

}

shortestPath.push(currentCityName);

return {

path: shortestPath.reverse(),

price: cheapestCityToValue[destination],

};

}Summary

In this part, we’ve gone through graphs and algorithms to deal with them.

- DFS - Recursion - Unweighted

- BFS - While loop - Unweighted

- Dijkstra - Altered BFS - Weighted

That’s it for this part. There will be one final part where I will use these on other use cases!

References